Problems. What is the purpose and meaning of risk management? Possible risks when organizing an event

The third step is to develop the actions you will take if the risks of your project are triggered. At the same time, the most important area of risk management is measures to prevent risks and minimize the likelihood of their occurrence.

All events within proactive risk s can be reduced to four main groups:

risk avoidance,

risk reduction,

taking risks,

· transfer of part or all risk to third parties.

Planning responding to risks - is the development of methods and technologies to reduce the negative impact risks on business company. This stage takes responsibility for the effectiveness of the protection business from the impact on him risks. Planning includes determining the actions that will need to be taken in the event of a risk event, identifying indicators by which you will know in a timely manner that the risk has worked, and assigning a person responsible for this risk. The effectiveness of response design will directly determine whether the consequences will be impacted. risk on project negative or positive (this is also possible).

At the final stage (monitoring and control) Risk management includes authorized persons responsible for each risk, whose tasks are:

· Ensure that the response system risks implemented as planned;

· Determine whether the response is sufficiently effective or changes are necessary;

· Identify the attack risks;

· Take necessary proactive measures;

· Do everything to make an impact risks turned out to be a planned and not a random result.

Main:

1. Abrams R. How to create the best business plan for any industry and field of activity. Forbes and Stanford Business School recommend / Rhonda Abrams. – St. Petersburg: Prime-EVROZNAK, 2008. – 382 p.

2. Burov V.P., Lomakin A.L., Moroshkin V.A. Business plan of the company. Theory and practice: Textbook. allowance. – M.: INFRA-M, 2009. – 192 p.

3. Collection of business plans for real organizations: practical work. manual / ed. Yu.N. Lapygina. – 2nd ed., erased. – M.: Publishing house “Omega-L”, 2009. – 310 p. 2007. – 304 p.

5. Ryabykh D.A., Gladky A.A. Business plan in practice. Experience of success in Russia. 28 implemented business plans (+CD). – St. Petersburg. : Peter, 2008. – 208 p.

6. Shash N.N. Enterprise business plan: practical. reference /N.N.Shash; edited by A.V. Kasyanova. – M.: GrossMedia: ROSBUKH, 2008. – 488 p.

Additional:

1. Barrow P. Business plan that works / Paul Barrow; Per. from English – M.: Alpina Business Books, 2006. – 288 p.;

2. Sutton G. The ABCs of drawing up a victorious business plan / G. Sutton; lane from English L.A. Babuk. - Mn. : “Medley”, 2007. – 384 p.;

3. Phil Stone. Business plan. Basics of business. Per. from English M.: HIPPO, 2004, - 112 p.

Nikonov V. Chapter from the book “Risk Management: How to Earn More and Lose Less”

Publishing house "Alpina Publishers"

Decision making problems: uncertainty, adventurism, indecision

The effectiveness of management methods is determined by the extent to which they increase the competitiveness of the people who use these methods and the organizations in which these people work. And the basis of business competitiveness lies in the decisions made by people. And it’s not the companies that are actually competing with each other; managers who work in these companies compete.

Of course, making effective and correct decisions is a key skill for managers. How effectively they implement the right changes (by developing new services, entering new markets, etc.), on how quickly and correctly they respond to external changes - and both cases involve decision making - depends their success and the success of their business.

Decision making, on the one hand, initiates changes, on the other hand, any change requires a decision (reaction). We ourselves need changes, but even if we don’t want changes, they will still happen regardless of our desire.

Some changes can be considered “favorable” (those that we ourselves initiate), some “not always favorable” (those that occur regardless of our desire). Favorable changes are necessary in order to earn more, but in other cases our task, as a rule, is to lose less.

Any change is associated with risks and problems and requires decision making. If we initiate changes, then by making a decision, we consciously change the future, which implies a certain level of uncertainty, and therefore risk. Suppose you traveled all the time by public transport (you didn’t have a car). What were your risks? The risk that the bus won’t come, the risk that it will be impossible to get on it, the risk that your feet will be trampled. We initiated a change and bought a car. The “old” risks have disappeared, but new ones have appeared: accidents, car theft, etc. Whether to initiate changes (and then manage the new risks that these changes will provoke) or not is everyone’s business. Perhaps some people find it more pleasant to mark time. But, of course, in order to achieve something, you need to initiate favorable changes and manage the risks that are associated with them.

When external changes occur, which are not always favorable, the manager’s task is to react to them as quickly and correctly as possible.

So, the fourth step of risk management is making decisions about the actions that need to be taken to ensure profit and security in an environment where “everything flows and everything changes.”

For example, we might miss information that the cost of the Pirate Ship attraction we are planning to purchase may increase. Analyzing market risks, we identified the risk of an increase in the cost of the attraction and made the appropriate decision - to fix its cost now with delivery in the future. This is an example of a decision to lose less.

Whether we create change ourselves or react to it, at the heart of the difficulties that arise in decision making lie three key issues that risk management helps solve: uncertainty, opportunism and indecision.

Uncertainty

The root of most of the problems that are associated with decision making is the uncertainty in which managers are forced to make these decisions. In some cases the level of uncertainty is higher, in others it is lower, and this factor largely determines the complexity of the solution.

How can you reduce the level of uncertainty? Firstly, the more information we have, the naturally lower the uncertainty and the easier it is to make a decision. Agree that when you are on a business trip in another city, choosing a place to go for dinner in the evening is much more difficult than when you are at home.

Secondly, decisions are easier to make in familiar circumstances. Even if you don’t know what will happen, you at least know what has happened dozens of times in similar situations.

Risk management acts as a substitute for such experience: by identifying risks, we compensate for the lack of information that we usually obtain “experimentally”. At the same time, by identifying the risks associated with making a decision and strategies for managing them, we collect all possible information that can help us make the right decision.

It would be naive to assume that uncertainty in decision-making can be completely eliminated - collecting all the necessary information is very difficult, and sometimes impossible. Often decisions need to be made quickly, in the face of a lack of information. Then, in order to make the right decision, you need to determine as accurately as possible the risks associated with these decisions. The more accurately we can predict possible scenarios for the development of events, the more accurately we can assess the risks, the more correct our decision will be.

Making decisions is taking responsibility. Moreover, most often you have to answer for other people (employees, for example) and to other people (shareholders), etc. The one who makes the decision is “responsible” for both success and failure. Taking responsibility in the face of uncertainty is not an easy task for many.

Two problems: adventurism and indecisiveness

In order to make decisions quickly and correctly, you need to eliminate two problems, which are based on uncertainty and fear of taking responsibility.

Problem No. 1. Managers take unnecessary risks: they make decisions and take responsibility for changes in situations where there are too many risks and these risks are unjustified.

Problem No. 2. Managers do not make decisions (they are afraid) when there are few risks and they are justified.

The first case is adventurism, the decision to act “at random.” In some cases this approach works, but this does not always happen. In any case, this is a situation in which we take responsibility when it is better not to do so - “we are not afraid when we should be afraid.”

The second case is indecision. We don't do what we need to do because we're afraid it won't work out. Or we don’t know which option to choose, because it’s not clear where the winnings are greater and the risk is lower. That is, “we are afraid when there is no need to be afraid.”

Both the first and second problems can be solved if risks are managed and correctly assessed when making decisions. Because properly assessed risks are the “definition of uncertainty.” And the right decision implies a competent determination of the “win-risk” balance and the ability to analyze possible scenarios for the development of events that you can provoke with your decision.

How does risk management in decision making differ from conventional risk management?

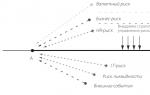

Assuming that we have a working business at our disposal and at one fine moment we stop, “fix the present,” determine point A and begin to consider the risks that are most important to us at this point in time (Fig. 1).

After that, we assess the risks and think about what to do so that in the future, at point B, we can earn more and lose less: what risk management strategies are best to choose so that the risks at point B do not interfere with us. Through our risk management actions we build a “shield” (Fig. 2).

Rice. 1

Rice. 2

To manage risks in decision making, we will need a more complex, two-step scheme.

Since decision-making is a choice from possible options for the development of events (scenarios), this scheme is based on an analysis of risks for each scenario. The basic idea is to choose the scenario that has the best benefit-risk ratio, given the actions that need to be taken to mitigate the risks associated with that scenario.

Making a decision and being at point A, we choose a scenario for the development of events and, thus, we can get to point B1 or point B2 (for simplicity, we assume only two possible outcomes) (Fig. 3).

Rice. 3

To understand how this circuit works, let's look at a simple example. You, while on a business trip, invite a colleague (also from another city) to dinner. Let's assume that both you and your colleague want to sit quietly and chat and have a tasty meal, but you have agreed in advance that you do not want to have dinner at a hotel. Let's say you find two restaurants - Japanese and Italian. You are comfortable with both Italian and Japanese cuisine, but you know nothing about your colleague’s tastes and cannot find out at the moment.

You have two scenarios (Fig. 4)

Rice. 4

Each scenario has two characteristics that interest us - the gain that you will receive if the scenario is realized, and the risks associated with this scenario. In the situation under consideration, the gain is determined by the wishes of the participants - “to communicate calmly and eat delicious food.”

Now, for each scenario, we identify the risks that will occur if this scenario is realized, as well as those risks that may arise during the implementation of the scenario (that is, the risks that the decision made will not be implemented).

Let's imagine that the first scenario comes true and you go to a Japanese restaurant. It may turn out that a colleague does not like Japanese cuisine. The food in the restaurant may be of poor quality. The restaurant may not be available. We can consider these three events as examples of the risks associated with a Japanese restaurant. When determining the risks in the second scenario, let’s assume that we have no doubt about the quality of food in Italian restaurants, but we are not sure that we will like the music in this restaurant; we will leave the other two risks the same as in the scenario with a Japanese restaurant.

Until now, we have not assessed the risks of the feasibility of the strategy: by identifying the risks, we assumed that the decision we made would be able to be implemented. The feasibility of a solution is a very important factor determining its success. In principle, something may not go as we plan for two reasons: either we chose the wrong scenario (path), or we cannot implement this scenario.

In our case, implementing the solution is a trip to the restaurant. What risks may be associated with this trip? Let's say that an Italian restaurant has just opened and few people know where it is located. A Japanese restaurant, on the contrary, opened a long time ago and everyone knows about it, but it is located in such a place that on the way there you can get stuck in a traffic jam for a long time.

As a result, we obtain the following picture of risks for each scenario (Fig. 5).

Rice. 5

Having imagined that the scenario has come true, and having identified its risks, we return back to point A and look at what can be done with each risk for each scenario - we determine risk management strategies. As a result, for each decision we will receive a set of actions. These actions will change the scenarios because we can now analyze the scenarios, provided that we have implemented all the actions aimed at managing the risks of this scenario. Thus, some of the previously identified risks will no longer be in the scenarios (we will build a “shield”) (Fig. 6).

We will receive two scenarios: B1" - "Japanese restaurant" and B2" - "Italian restaurant". Scenario B1" means that we make a decision to select a Japanese restaurant and implement all actions aimed at managing the risks associated with this scenario.

Rice. 6

What actions will constitute a “shield” in each scenario? To accurately assess risk parameters and understand what can be done about them, it is necessary to collect as much useful information as possible. We can try to find out whether a colleague likes Japanese food or prefers Italian food. We might also try to find out how popular both restaurants are and how likely it is that there will be no seats. If you have the opportunity to ask your colleague how he feels about Japanese cuisine, and he says that it is positive, then the likelihood of this risk occurring can be defined as zero. Thus, by collecting information to assess risks, you eliminate one of them.

Let's say you interviewed your friends and found out that half of them, when trying to get into a Japanese restaurant, were faced with a lack of empty seats. Accordingly, the probability of this event can be assessed as “average”. At the same time, only one of your interlocutors admitted that after visiting this restaurant he had health problems, but you did not hear any other complaints about the quality of food. Therefore, the probability of this risk can be assessed as “low”, and the impact, naturally, as “high”. By looking at where the restaurant is located, you were able to assess the likelihood of being caught in a traffic jam as high. But since, if the risk materializes, you will still be able to communicate in the car, the impact of the risk can be considered “medium”. Then we will have the following risk assessment picture for a Japanese restaurant (Fig. 7).

Now we do the same trick with an Italian restaurant (Fig. 8).

Rice. 7. Risk assessment for a Japanese restaurant

Rice. 8. Risk assessment for an Italian restaurant

We must remember that actions aimed at mitigating the risks of the scenario we choose must become part of our decision, that is, part of the scenario. Therefore, before we begin to implement a solution, we identify risk management strategies and begin to implement these strategies. The risk that your colleague will not like the kitchen can be mitigated by simply asking him what he likes. If this is not possible, then you should think about where to get information that can help you. Let’s say you know for sure that a colleague is loyal to Japanese cuisine, but about Italian you could only find out what you “most likely like.” To mitigate the risk of lack of empty seats in a restaurant, you can use a hedging strategy - reserve a table in advance, that is, fix a parameter that may change (the parameter in this case is the availability of empty seats). If this is done with both restaurants, this risk will be completely mitigated. You can simply accept the risk that your colleague will not like the music. In order not to get stuck in a traffic jam, we can take the metro - this way we can avoid this risk (although this will also change the size of the winnings associated with this scenario). The risk of not being able to find a restaurant can be mitigated by finding a map or using a GPS navigator.

But the risk that food may be of poor quality is not clear how to mitigate. Therefore, it is better to either avoid it or accept it. Then we will have the following picture of the actions associated with each scenario (Fig. 9).

Rice. 9. Picture of actions for scenarios B1" and B2"

By identifying the risks for each scenario and the actions that need to be taken to mitigate these risks, we will obtain new scenarios B1" and B2" with new payout amounts and risk levels.

We compare them and choose the one that has the minimum risk and at the same time gives us the maximum gain. In the case of a Japanese restaurant, the risk of not liking the food is completely mitigated, but we do not know what quality of food there will be. In the case of an Italian restaurant, there are no problems with quality, but we don’t know for sure whether a colleague likes Italian cuisine or not.

The risk associated with food quality, even though it has a low probability, is very significant. Therefore, the optimal solution would be an Italian restaurant. But if you want to take a chance, you can accept the risk of “poor food quality” and go to a Japanese restaurant.

Risk management when making decisions is very disciplined and ensures that decisions are not made at random. On the contrary, all necessary information will be taken into account, all possible obstacles will be analyzed. This means you won't choose a scenario before you've developed an action plan for each risk. Therefore, you will protect yourself from choosing a scenario that contains an unreasonable amount of risk, and will not refuse scenarios that actually do not contain risks.

Example: changing the payment system in a park

Let's consider another situation in which a decision needs to be made - the decision to change the payment system in the park.

The investor finally decided to take a break. To “combine business with pleasure,” he took his grandchildren and took them to Amusement Park.

He liked it there, and he was once again convinced of the correctness of the investment.

He noticed that the payment system in this park was structured differently: if in our country people paid a symbolic amount for entry, and then bought a ticket for each attraction, then here they had to pay a significant amount at once, and then use any attractions without additional payment .

When he returned, he instructed his team to decide on the advisability of switching to a similar system. Park management began collecting information. There weren't many statistics, but here's what they managed to find out.

- The park's income consists of the following components:

Attraction fees (70% of income);

Income generated by the cafe (15% of income);

Entrance fee (5% of income);

Income from the sale of souvenirs (10% of income).

- The cost of all attractions is the same.

- There are often queues at the ticket office at the entrance. The attractions are unevenly loaded - there is a queue for the roller coaster and the Ferris wheel, while other attractions are often idle.

Definition of the situation

As in the example with restaurants, when deciding to choose a payment system in a park, we must define as fully as possible the situation in which the decision is made.

The original data were presented in the inset. Now we need to formulate the result that the park management wants to get from implementing the solution. Let's assume that the park management is interested in:

- the rides had an even load;

- there were no queues at the cash registers;

- there was no non-target audience in the park visiting only the cafe;

- sales of souvenirs (an important marketing tool) increased;

- clients could know in advance how much they would have to pay for their vacation;

- Either decision did not reduce the park's total revenue.

Defining Strategies and Scenarios

Making any decision related to initiating changes involves analyzing at least two scenarios: leaving everything as is and implementing the change. In our case, "keep it the same" means maintaining the current system where customers pay a small amount at the door (which is 5% of the park's total revenue) and then buy tickets for each attraction. Now let's look at two scenarios for changes that park management can initiate.

- Introduction of the “Single Ticket” system: the client pays a significant amount at the entrance, but has unlimited access to the attractions.

- Free entry: remove the nominal entry fee and make entry to the park free.

Risk assessment by scenarios

Let’s imagine that the “Single Ticket” scenario has been implemented, that is, a single entrance fee has been introduced in the park. It is logical to assume that this will be a significant amount, but, naturally, less than the cost of visiting all the attractions separately. What risks arise in such a scenario? First of all, we will analyze the business risk, that is, the risk of changes in demand for services and the associated decrease in income. With such a payment system, customers who come only for one attraction, and those who come only to sit in a cafe, will no longer come to the park. Thus, there is a risk of a decrease in the total number of visitors - a single ticket may simply “scare off” part of the customer base. Next in the classification of risks we have considered are market and credit risks: a change in the payment system in the park is unlikely to affect these types of risks, but it certainly makes sense to analyze operational risks in more detail. As an example of an operational risk, consider the “Line at the cash register” risk. Even if the total number of visitors decreases, the queues at the box office, although they will become shorter, may well remain the same.

The impact of the “Change in Demand” risk will be high, since it can lead to a decrease in profits if we are unable to compensate for the part of the income that we received from customers who will not come to the park under the new system. The likelihood of this risk occurring can be assessed by calculating what share of the income structure we will lose. Let's assume that, after conducting additional research on the existing customer base, we assessed the likelihood of this risk as low (this is possible if most of the customers under the current system come to the park to ride the rides and visit more than one ride).

The impact of the Queue at Entry risk can also be considered high, since for the majority of customers, standing in line to pay a significant amount for a single ticket is much more unpleasant than standing in line to pay a nominal entry fee. But in this scenario, visitors will know exactly how much money they will have to spend on attractions.

Now imagine that we have implemented the second scenario - “Free entry”. What risks await us in this case? Analyzing the business risk, we can see that with free access to the park, the number of representatives of non-target audiences will significantly increase. The impact and likelihood of this risk are high, because the non-target audience will make the stay in the park less comfortable for those who came with children to ride the attractions. The share of attractions in the income structure significantly exceeds the share of cafes, so it would not have been possible to compensate for the losses of the target customer base in any case. The probability of this risk, taking into account the conditions of Russian reality, can safely be considered high.

There is also a risk that in this scenario, attractions will be unevenly loaded, with visitors favoring roller coasters and the Ferris wheel. Assuming that the cost of all attractions is the same, this scenario will certainly result in lost profits, and the impact of this risk can be considered high. Another point is that in a situation where customers have a choice of what to spend money on - on a souvenir or on an attraction, they will most likely choose the attraction. This also needs to be considered a risk, since one of the requirements of the park management is “that souvenirs be bought.” But in this scenario, the total number of visitors will increase (since there will be no barrier at the entrance), which will have a positive impact on the popularity of the park. It is also necessary to take into account that if someone, even by chance, looks into the park, then it is likely that he or she will ride one of the attractions simply out of curiosity.

All we have to do is identify and assess the risks of the “leave everything as is” scenario. These risks are the easiest to identify; to do this, you need to analyze the current situation. We can use the background information to identify three risks: queues at the entrance, uneven loading of attractions, and the presence of unwanted crowds in the park (although a small entrance fee reduces the likelihood of this risk occurring).

Now that we have identified and assessed risks for all scenarios, we can proceed to the most important step - choosing a risk management strategy.

Selecting Risk Management Strategies

Let's look at risk management strategies in the Single Ticket scenario. The risk of a decrease in the overall flow of visitors and the associated decrease in income must be mitigated, even though we have determined the likelihood of this risk to be low (lost cafe income is compensated by increased income from attractions). Here you can use various promotional tools, promotion on radio and in newspapers.

The risk of queues at entry can be mitigated by increasing the number of ticket offices and providing the ability to purchase tickets online. You can also create a system of mobile cashiers who will meet visitors as they approach the park and sell them tickets. You can also organize a payment system in such a way that visitors can pay themselves with a credit card.

Carrying out promotions and increasing the number of checkouts at the entrance will require a significant investment, and this must be kept in mind.

What can be done about the risks in the remaining two scenarios and how will these actions change the “baseline” scenarios? Some of these risks overlap, and we will consider each of them in only one of the scenarios.

In a Leave It As Is scenario, the risk of uneven occupancy at attractions can be mitigated by increasing the cost of popular attractions (pre-pricing them so that total revenue does not decrease) and advertising attractions that are less popular. Mitigating the risk associated with entry queues can be exactly the same as under the Single Ticket scenario.

The risk of non-target audience members entering the park can be mitigated by installing face control at the entrance. A special promotion program can be organized for souvenirs, and part of the income lost due to the elimination of entrance fees can be compensated by increasing the cost of attractions.

These examples only demonstrate the principle of risk management in decision making, and in no case the technology of operating an amusement park - you may have other ideas, see other risks and other ways to mitigate them. The main thing is that whatever actions are aimed at managing the risks associated with each of the scenarios, they must be included in the action plan and be part of the decision that you make. And it is important to remember that after the risk is realized, you will have other risks that will need to be managed in the same way.

New scenarios associated with the risks of an amusement park no longer contain the risks that could arise during the implementation of “basic” scenarios. All we have to do is compare the scenarios and compare them with the requirements that we defined earlier.

We assumed that the park management wants the attractions to be evenly loaded, that there are no queues at the ticket office, that there are no unwanted visitors in the park, that sales of souvenirs increase, that customers know in advance how much they will have to pay for their vacation, and that any decision will not the park's total income decreased. The “Single Ticket” scenario best meets these requirements, and the risks that will lead to failure to meet these requirements, provided that actions to mitigate them are taken, are the least included in this scenario. But if park management had made a decision right away without analyzing the risks, it is quite possible that the changes would not have been exactly what was expected. Now that we have a very specific plan of action to mitigate all the risks associated with this scenario (and these actions are part of the decision we make), we can be confident that this decision will provoke exactly the changes we need.

Risk Management in Decision Making - Summary

- Risk management helps you make the right decisions and avoid situations:

When the right decision is not made because we feel it is “too risky”;

When a wrong decision is made because there seem to be no or minor risks.

- When making decisions, formalize possible scenarios for the development of events. Imagine what risks you will have if each of the scenarios comes true.

- Also analyze the risks that may arise during the implementation of your decision. The right decision is not only the right one, but also a feasible scenario.

- Identify actions you can take to reduce risks. These actions should be part of your decision.

- Consider new scenarios, provided you have implemented risk management strategies for each scenario.

- Choose the scenario that will give you the maximum level of winnings with the minimum level of risk. The key is to remember that actions to mitigate scenario risks should be part of your decision.

17.02.2011

The next risk management conference will be held in July 2013

More and more energy companies are developing risk management systems. They are driven not only by the requirements of regulatory authorities, the consequences of the crisis, energy accidents, but also by the desire to lay the foundation for business development. Therefore, it is so important to build a system for detecting risks and taking advantage of opportunities, as well as early response to threats.

DTEK Group has been operating in the Ukrainian energy market since 2002. It includes 15 enterprises that form an effective production chain from coal mining and processing to the production and supply of electricity. Until 2009, risk management in the company was a system in which risks were tied only to functional areas - business lines. In order to make the system more understandable, transparent at all levels and effective, its concept was revised in 2009. At that time, the risk management department was subordinate to the financial director for some time; during the crisis, it was removed from the subordination of the general director for a clearer focus of efforts. When management saw that the company had the pre-crisis level of stability, it was decided to make structural changes again. So the risk management function was transferred to the executive director. In addition, a group risk committee was created, which included the CEO, CFO, security director, as well as the heads of three departments: risk management, audit and compliance. The committee’s task was to transform the existing risk management into an effective tool for managing risks and increasing the reliability, transparency and efficiency of company management.

First of all, the purpose of the system was reformulated. We have identified six areas for ourselves:

- checking objectives and strategic initiatives for relevance;

- checking goals for achievability in the short and long term;

- providing reasonable confidence in achieving goals (answering questions: what can help us or, conversely, hinder us; how we can reduce possible obstacles and potential problems and turn them into opportunities);

- work on mistakes; monitoring events, drawing conclusions and changing future behavior to a more effective one; maximum flexibility;

- development of a culture of risk management in everyday activities - that is, a kind of foundation for the functioning of the system, not only risk management, but also effective management as such, where responsibility and rationality are present in every area of the enterprise.

The most important thing in a risk management system is to ask key employees the right questions in a timely manner, and then collect and analyze the answers and communicate them to everyone else.

The next step was to clearly structure the risks into groups, including identifying two large groups of risks: internal and external. There was no such division before. And only external risks fell into the category of the most significant risks for the company. Internal ones were not carefully considered, which made it sometimes difficult to unlock the potential that the company had and improve internal processes. In order to balance our efforts to deal with external and internal risks, we have implemented such a division.

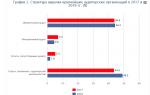

Risk groups are tied to groups of goals, and each specific risk is tied to a specific goal and target measurable indicator: short-term (operational), long-term (strategic) and always existing (systemic). Based on this, DTEK’s risk structure today looks like this:

Systemic risks include:

- risks associated with personnel management;

- legal risks;

- political risks;

- risks associated with information technology;

- asset security risks;

- other risks threatening the existence of the company.

Risks assigned to strategic areas of activity:

- reputation risks;

- investment and long-term liquidity risks;

- environmental risks;

- compliance risks;

- risks of strategic projects (including M&A);

- market risks (risks of competition and market environment);

- other risks directly related to the execution of the strategy.

Some of the operational risks include:

- risks that may interfere with the implementation of budget objectives;

- risks of investment projects within the current period;

- tax risks;

- risks of current business plan projects.

I would like to note that during the year, risks from other groups – strategic and systemic – may also fall into the operational category. We identify them at the annual assessment stage for inclusion in the annual action plan.

The described structure is quite flexible and is in a constant process of improvement and updating.

Why was it decided to link risks to goals? In a company, each area of activity, function, and employee has a list of goals for the year. In addition, there are goals for a longer period (say, strategic), in the case of long-term projects. Thanks to such transparent communication, everyone understands what they must achieve, by when, and how the result can affect the work of the entire group. This not only improves the clarity of goal setting and reporting, but also motivates and promotes greater employee involvement in the process.

Process, indicators and appetites

The company has adopted a management and risk assessment cycle that is repeated from year to year. In addition, the strategy and strategic risks are updated annually. We realize that the market does not stand still; many external factors affecting business change. This entails the need to revise goals and objectives, as well as the risks associated with them.

The basic steps of the risk management process are always the same. They include identifying and defining the types and types of risk, the causes (factors) of its occurrence, assessing the inherent risk, establishing appetite, developing management measures, assessing residual risk, and monitoring.

To obtain a quantitative statistical assessment, our company uses risk exposure meters, the so-called key risk indicators ( KRI – key risk indicator). This is a quantitative indicator that allows us to judge the level of actual exposure of a company to a given risk at one time or another. Dynamics KRI is monitored periodically without fail. Let me give you an example: the breakdown rate of equipment (as an operational risk) has measures in the form of the number of breakdowns, losses from downtime of the work process and restoration of normal operation, restoration costs, etc.

Of course, not all risks can be quantified. Some of them, such as reputational or environmental risks, are often assessed qualitatively. In this case, we add alphabetic encryption to the digital value (for example, the possible occurrence or non-occurrence of various types of liability, etc.).

Appetites have been established for all risks. These are quantitative indicators - boundaries that determine the maximum acceptable level of risk that the company is ready to accept (before the need to implement corrective measures). At DTEK they are two-level.

The first level is those appetites that are formed from indicators. For example, if the staff turnover indicator is less than 10%, then the situation is within normal limits, and no special measures in the form of analyzing what is happening and introducing additional incentive measures are required.

The second level of appetite is established for aggregate indicators, that is, those indicators that are affected by risk. In our company it is EBITDA. In the process of approving the risk appetite for this indicator, members of the DTEK board expressed their proposals: they named the amount the loss of which would be acceptable for the company and discussed it, and based on the voting results, the risk appetite for EBITDA for the entire group in 2010 was set at 5%. After this, for each enterprise, its appetites were calculated and reported in monetary terms, proportional to its contribution to this indicator. What does this mean? If the deviation of the actual EBITDA of one or another enterprise from the planned business plan within a month is less than the established figure - a special analysis of the reasons for the deviation may not be carried out, or may be carried out only upon request. If the deviation turns out to be higher than acceptable, our enterprises, along with reporting on the implementation of the plan, provide us with a description of the reasons for the deviation, the risks and factors that caused them, as well as a list of measures taken and proposals to prevent similar problems in the future. This is an established process that we call budget control. At the same time, in essence, this is an elementary management of risk appetites at the level of the parent company and their standard tracking.

In addition, once a month all our enterprises provide reports on the implementation of risks. If the corresponding indicator goes beyond appetite, then they simultaneously send us an analysis of the reasons why this happened and a list of measures that will be taken to prevent a similar situation in the future. Reports are periodically reviewed by the risk committee and are constantly monitored by our department. However, if we see that such and such a risk is constantly at the limit of appetite, but has not yet gone beyond it, we quickly take control of it and develop measures that will prevent this risk, which will be discussed later.

Transformation into opportunity

In general, the picture of risks for the company and its areas of activity is reviewed once a quarter at a meeting of the risk committee. In addition to the management team of the corporate center, top managers of enterprises belonging to the DTEK group, as well as their key employees, also take part in it. We divide risks into significant (group A) and insignificant (group B). A group of the most significant risks that can greatly affect our business is always brought up for discussion at the highest level. They are identified based on interviews with experts, including from specialized directorates, the strategy directorate of our group, analytical data provided by enterprises, the strategic block and prepared by risk managers, publications in the media, as well as internal statistical information. The materiality of the risk can be determined relative to a monetary threshold, and such materiality limits have been established for the enterprises of our group. In addition to the materiality threshold, the expert opinion of a member of the risk committee is taken into account. For example, if some risk does not fall into the group of significant ones in terms of monetary value, but we are aware that it is important for the company, the risk committee brings it under control and works with it.

As an example, for DTEK one of the biggest risks today is legislative changes. The energy sector in Ukraine is subject to strict regulation, and each new law, regulation or order can have serious negative consequences for the company.

Each of these high-level risks is analyzed and monitored quarterly at the committee level and monthly at our department level - we track the trend, the level of appetite for it at the moment, etc.

It is constant monitoring that serves as a powerful risk warning tool. For each function of our enterprise, all data is consolidated, a cross-section of the company is compiled: statistics in different sections, graphs, forms and analysis. The analysis includes, in particular, comparison with previous periods, with established risk appetites for each indicator, with the achievement or failure to achieve goals. For example, we have assessed the current “operational” level of accidents, and in our business plan we annually include an amount for restoration based on the results of accidents - we know from statistics that they will still occur in some, albeit minimal quantities. Throughout the year, we collect information about breakdowns, look at the dynamics in comparison with previous periods, and compare them with the figure included in the business plan. We monitor so that their volume does not exceed the established appetites. The most important part is to analyze the causes of accidents and the measures taken. We look at why certain developed measures do not produce results, and if they were not implemented at all, what were the reasons, and insist on their development, etc. After this, all the data we received and processed are presented in the most convenient way visible to interested managers in the form of graphs, trends and analysis. We are currently automating the work with such reports.

In general, during risk committee meetings, we try to present our problems as our opportunities. The group's management initially views risk as an uncertainty that can give the company positive potential, and not as a problem from which it is necessary to shield itself. An example would be situations with changes in regulatory requirements: suppose a specific regulation may have a negative impact on our generating unit. Before its approval, we already consider all available possibilities and try to understand whether, say, distribution or production can benefit, how to balance the work, etc. As a result, we try to use any change wisely in any case.

Of course, our company is not limited to identifying and assessing just a few significant risks mentioned above. We also identify and monitor dozens of smaller risks. All of them are considered at the level of enterprise management - the corporate center delegates to them both the opportunity and responsibility to manage risks within the framework of those appetites that exist within the entire group.

It's all about the reaction

In general, we do not create overly detailed risk response scenarios. At the same time, we have formulated a standard list of our actions in the event of a risk event occurring. When the value is output KRI beyond the border established by the risk appetite, the risk owner initiates one or more actions from the following list:

- taking emergency measures to reduce/close the risk;

- review of the action plan aimed at reducing risk exposure with mandatory notification of the risk committee;

- review of business plan/targets;

- review of risk appetite and informing the risk committee (when reviewing significant risks).

Some of the response options described above are often already contained in a worst-case scenario plan (and a global example of this is the disaster recovery plan that a company is developing today).

Measures can be developed by the risk owner if the appetite is exceeded in a clearly limited period, if, for example, the realization of the risk is temporary and associated with the momentary situation on the market, a temporary resolution of the regulatory body or a specific accident. This happens most often, and such an action is mandatory, since it means that the previously provided measures are insufficient to prevent losses from the realization of the risk. In other, rare cases, if the realized risks are protracted, systemic or catastrophic in nature, we may revise the appetite for them or even the company’s business plan (that is, new targets will be developed). An example of such a risk being realized was the financial crisis.

If risks that exceed the threshold and occur repeatedly do not entail significant consequences, a revision of the risk appetite value may also be initiated. In this case, we realize that we may have set the target too harshly.

Reasonableness and responsibility

What exactly is the risk management department responsible for? Using DTEK as an example, I can say that we are responsible for the risk management process (and not for specific areas of the company’s activities and the risks in them). Our task is to make it as effective as possible. Our division is responsible for the functions of methodological support, consolidation of all information on risk management and its analysis (in addition to additional related areas of insurance and internal control).

As for me as the head of the function, I am not responsible for the risks themselves, their implementation or prevention. Moreover, quite often they are related to the production process, finances, etc. My task is to conduct appropriate training for key specialists, collect the necessary information, structure and analyze it, submit it to managers on time, build a system of indicators, etc. But as the head of the internal control and insurance service, I am responsible for reasonable and optimal insurance in the group. Here I am also the owner of the process, so not only the development of methods, insurance requirements, determination of the list of counterparties and other related tasks, but also the direct effectiveness and results of such work are within my competence.

In general, the purpose of our function is to provide information for reasonable and responsible decision-making, that is, timely provision of a complete picture of risks, opportunities, history and assumptions to responsible persons - managers. This includes early warning of problems, analysis of how they were solved in the past, and much more, the mechanics of which were discussed above.

At the same time, the risk management department does not independently review internal processes. I initially insisted on not making our division a department for improving operational efficiency and optimizing business processes. This is done in the group by specialized directorates, responsible working groups and managers. We participate in relevant events as methodologists, moderators and, of course, as risk management specialists. We find out what was the reason for the risk to occur in the past (whether the factors that caused it remain) and today (where there are unclosed areas), and together with our colleagues we try to figure out how to prevent problems in the future. This is precisely the competence of our internal control function.

Today, risk management in the DTEK Group is a fully integrated function into key business processes. It employs 14 people. We have developed and approved at the level of the board and other authorized bodies a risk management policy, relevant methods and regulations in areas, forms of reports and plans. We review and agree on the list of risks, their assessment and the risk prevention and response plan before it is discussed by the risk committee and other relevant committees and authorized persons. Our department processes all relevant final reports prepared by group managers for senior management.

To summarize the above, I can say: over the year and a half of its existence, the updated risk management system at DTEK has made the decision-making process more transparent and simpler for managers. I hope this has contributed to improving their quality. Thanks also to the effectiveness of our management decisions, we maintain a strong position in the fuel and energy market of Ukraine. I have no doubt about this.

Irina Andropova, Head of the Internal Control and Risk Management Department at DTEK

Organizing events is a complex and sometimes unpredictable matter. At almost all events, situations arise when something does not go according to plan and gets out of control. There are many risks associated with organizing events, and we will talk about them in this article.

- Staff

People are always a source of risk. Even if you work with professionals, you should not exclude the human factor. The presenter may get sick, the speakers at the event may not come, the waiters may not be able to cope with the work. You should always have the phone numbers of people who can quickly come and save the situation. Numbers for presenters, emergency services and food delivery will never be superfluous, and in some cases they will help save the entire event from failure.

- Equipment may break down

It is necessary to remember that the camera or camera may run out of battery, the computer or projector may stop working, and the electricity may completely turn off. Such situations should always be anticipated in advance. Carefully supervise the work of your contractors, check all equipment in advance, and always have several cables and extension cords in stock. You never know when you might need them, but in case of force majeure they will help you a lot.

Before the event itself, check with the site owners to see if they have a spare generator. If not, then you need to find out if there are people who can quickly troubleshoot problems.

- Speakers at conferences

Check your guest speakers in advance for public speaking experience, otherwise you may end up in a situation where the speech becomes a failure due to the speaker's lack of experience. In this case, rehearsals before the event will save you, which will help an inexperienced speaker prepare for the stage and save you from unforeseen situations.

- Sudden weather change

There is always the possibility that at the most unexpected moment it will rain or thunderstorm. And you must be prepared for this. Think in advance about what you will do in this case, where the guests of the event will have to go. If the start of the event depends on the weather, then you need to think about how much time you can postpone the start, and how you can occupy the people who have gathered for the beginning of the holiday at this time.

- Guests may not behave as planned

The event manager’s event plan clearly states everything that should happen at the event: when the next speaker at the conference comes out or when it’s time for a “surprise” for the guests of the holiday. Sometimes guests may not pay attention to a request to go somewhere because they are too carried away by the conversation, accidentally ruin a key decoration, and so on. Therefore, you need to remember that this plan is only in front of you and guests do not think about timing and how complex the event they came to is organized.

Material prepared:

Great events. Technologies and practice of event management. Shumovich Alexander Vyacheslavovich

Main risks

Main risks

The main risk is related to failure to carry out your own plan. It may turn out that a wonderfully developed scenario, systems of measures to prevent problems, etc., will simply not be implemented by your subordinates.

To prevent this from happening, it is necessary to confirm from each team member that he is familiar with the established procedure and rules, as well as what responsibility he bears for failure to comply with them.

There are also risks associated with participants. At events, adults with higher education often begin to behave like children. They get lost in three rooms and cannot find a toilet (although they have traveled half the world and know how to navigate in unfamiliar surroundings), intensively lose their own things, accidentally take someone else’s... This is not their fault, so this factor must be taken for granted and taken into account in their work.

Necessary qualities of an event organizer:

– calmness. You are ready for anything, all options have been calculated, and you know how to behave. And your team knows;

– attentiveness. The power of little things is that there are a lot of them. Don't overlook anything.

– friendliness. Whatever happens, your guests are your Clients, and they should be treated as friendly as possible;

– resourcefulness. Even if you have not prepared an option for the current situation, you must be firmly confident that you will quickly find an acceptable solution;

– competence. Knowledge of your event and all its components, experience, and attention should convince Clients and customers that you will solve any problem. And you must believe it too;

– "paranoia". Stay alert at all times.

A special focus is “paranoia”. She will save you. Let's start with Murphy's laws: “If trouble can happen, it will happen. If several troubles can happen, they will happen in the most unfavorable sequence.”

Accept this - THIS IS NORMAL in our business. In the sense that this is the norm.

Break your event down into its component elements. Think and make a plan for yourself what to do if each of these elements falls out. One, two, three, two in a row. The most incredible things can happen. Think about what you will do in different situations.

Find key element(or several) of your event, which can ruin EVERYTHING. There is almost always one. This is exactly what you should prepare for, check and double-check everything so that this does not happen.

You must have a backup plan for every possible problem. Least psychologically you must be prepared for anything. Even if your plan to save the situation does not compensate for the losses, the event will not be completely disrupted. Someday this approach - preparing a backup plan - will save you. This is professionalism.

Computer risks when holding an event it is worth considering separately.

It is known that equipment tends to break down; accordingly, it can break down during the event. The computer may freeze. It may turn out that the program needed by the presenter does not work or is not installed. To avoid this, use duplicate copying. Copy all the data you need (lists, presentations, etc.) to a CD, to a flash drive, and have a spare computer with you.

In the office, to reduce the risk of data loss, install a server where all event data will be stored, and regularly copy all necessary and event-related information there. If someone's computer breaks, you'll lose data in just one day (if you back it up daily).

We have a spare set of necessary equipment, which we “pointlessly” carried to every major event for several years. And at one of the conferences our computer burned out right during the presentation. It sparkled, smoke came out, and everything turned off. What to do?

We just replaced the computer. We had a spare. All the necessary presentations were recorded on it, in particular the presentation of the speaker during whose speech the incident occurred. Our manager was in the hall, and he reported what had happened to the “problem solving table” via walkie-talkie. The replacement took a few minutes, and the speaker only missed a couple of slides.

Nothing like this happened for ten years. But when it happened, we were ready. I am proud of this.

From the book Logistics: lecture notes author Mishina Larisa AlexandrovnaLECTURE No. 10. Risks in logistics 1. Essence and content, types of risks In any practical implementation, the logistics system, from the process of cargo movement to the processes of moving orders in the market space, covers a large number of heterogeneous aspects, work

From the book Fundamentals of Project Management author Presnyakov Vasily Fedorovich From the book Innovative Management: A Study Guide author Mukhamedyarov A. M. From the book Business Plan 100%. Effective business strategy and tactics by Rhonda Abrams From the book Work Like Spies by Carlson J.K.Cost risks Most of these risks are the result of errors and omissions made during scheduling and technical

From the book Project Management from A to Z by Richard NewtonRisks of price protection. In projects that have a long period of implementation, it is necessary to provide measures in case of price changes - usually increases. When revising prices, it is necessary to avoid using one large amount to cover all price

From the book Informatization of Business. Management of risks author Avdoshin Sergey MikhailovichTechnical risks Technical risks are problematic and can often lead to the closure of a project. What happens if a system or process does not produce results? Contingency plans or backup plans are drawn up in cases where there are